John McCulloch compiled folders of archives that resonate deeply with me—reminders of a time when we routinely photocopied inspirational images, book chapters, and cut-out newspaper or magazine articles, keeping them as significant reference points to return to.

Looking back on my journey in the Creative Industries, one thing has always driven me: solving problems. This is a fundamental principle of creative practice-based research. Every day, I see opportunities to address challenges through creative practice — opportunities to transform human experiences, whether small or large.

Creative practice is more than ideas; it’s about making them happen. This requires experimentation and refinement. Nothing new is born from simply following conventions. If you always stick to what you already know, you risk stagnation. You will face doubt, uncertainty, and setbacks — but the trick is not letting this stop you.

Don’t be afraid to do things you have never done before — this is where growth begins. Start small, take risks, and experiment with materials, methods, and approaches. Each step expands your understanding and reveals possibilities you couldn’t have imagined. Never stop learning, and you will never stop growing.

Don’t worry about what others might think of your work. Everyone has an opinion, and the opinions of those who do not understand your journey are often the most negative. Some people fear risk and cling to the status quo — that’s okay. It doesn’t mean you have to. There is greater joy in solving a problem than continuing to replicate a problem that already exists.

Start building a network of people you admire. Connect with peers at the same stage as you, as well as leaders in your field. They can support and advise you, offering insights that will help you navigate challenges along the way. Problem solving, whether big or small takes a community. Listen to those who have earned your trust and respect and let their guidance inform your practice.

Work with others who share your vision. You can achieve more together than alone. Conversely, don’t spend energy working with people who don’t share your vision — banging your head against that brick wall will only deplete your energy. Collaboration is essential, but it only works when everyone is aligned and committed to a shared purpose.

The outcomes of creative work can be modest — a small impact within a community — or significant, creating sustainable change. What matters is embracing the process and getting your work out into the world, no matter your age or experience. The initial plan will evolve as you progress, shaped by learning, experimentation, and collaboration.

Creative practice is about seeing problems, exploring possibilities, taking action, and learning as you go. It’s about letting go of constraints, discovering freedom in your work, and making a meaningful impact along the way.

So, go forth and create!

As I continue delving into the archives for the exhibition 'Drawing Together: John McCulloch’s Community Architecture', I’m struck by how clearly McCulloch understood something we still struggle with today: towns and cities should first and foremost work for the people who walk through and around them.

In his 1975 University of Auckland thesis, 'Invercargill: A Study of the Town Centre', McCulloch placed pedestrians at the centre of his thinking. He argued that the heart of a town or city is defined not by cars or buildings, but by the everyday activities and experiences of the people moving within it.

His thesis focused on revitalising Invercargill’s town centre—creating a sense of identity, a true ‘arrival’ point, and a civic heart shaped around pedestrian activity. Shelter from the weather, clear walkable routes, green space, trees, places to sit, places to gather—simple, human-centred elements that make a town or city feel alive.

Re-reading his work makes me reflect on my own daily experience as a committed pedestrian. I navigate cars reversing out of low-visibility driveways, unlit paths, damaged pavements, broken glass, scooters, and spaces that feel increasingly designed for vehicles first. The sense of abandonment in some pedestrian and cycleway areas stands in stark contrast to the vibrancy McCulloch envisaged.

One passage he quoted in his thesis, taken from Ilf and Petrov’s satirical novel 'The Golden Calf', feels surprisingly contemporary in its lament of car dominance over pedestrian space:

“The streets built by the pedestrians passed into the hands of the motorists. The roads were doubled in width and the pavements were narrowed down to the size of a tobacco wrapper. In a large city, pedestrians lead the life of martyrs, just as though they were in a traffic-run ghetto. They are allowed to cross the street only at crossings – at points where the traffic is heaviest and where the thread by which a pedestrian’s life usually hangs may most easily snap.”

Written nearly a century ago, it still reads like a critique of many modern towns and cities.

McCulloch believed Invercargill—and all towns and cities—should offer a welcoming, human-scaled centre: a place where walking feels safe, accessible, intentional, and valued. His early advocacy for pedestrian-first design now feels less like historical research and more like an urgent reminder.

The exhibition research keeps me returning to this question:

What would our towns and cities look like if we loved pedestrians again?

Ilf, I., & Petrov, E. (1964). The Golden Calf (J. H. C. Richardson, Trans.). Frederick Muller. (Original work published 1931).

Before you sign up for a programme of study, start with the most important question: what kind of work do you want to do? If you’re not sure yet, that’s completely normal. A bit of research will help you figure it out.

Begin by looking at real job listings across areas that interest you — animation, design, film, gaming, content creation, photography, music, or any other creative fields. Pay attention to what roles spark your interest, the skills employers are looking for, and any patterns that show up across different jobs. If you spot a role that feels like your ‘dream job,’ reading the position description carefully can give you a clear idea of the skills you’ll want to build through your training.

Once you’ve collected a few examples, make a list of the skills that appear repeatedly. Creative industries change fast, but the skills employers consistently ask for give you a strong indication of what is currently in demand. This list becomes your starting point for figuring out what type of training will support your goals.

It’s also important to remember that studying is a major investment — not just financially, but also in time and energy. Once you know what skills you’re aiming for, compare different programmes and check how well they align with the direction you want to take. You want to be sure the training fits your needs, your interests, and your aspirations.

When looking at different options, choose programmes that are genuinely connected to the creative industries. Look for tutors or facilitators who are active in the field — people who are working professionals, researchers, or creators with up-to-date knowledge. Most institutions list staff bios on their websites, and these should clearly show industry engagement. Learning from people who work in the sector means you are more likely to gain relevant, current skills.

It’s also worth asking whether the programme has industry advisory groups, partnerships, or alumni networks that are genuinely involved in shaping what is taught. These networks help ensure that your learning reflects real-world expectations and give you valuable opportunities to meet the people who are already doing the work you want to do. Alumni networks can help you see the many different pathways graduates take and can give you insight into how people build sustainable creative careers.

Real-world learning is another essential component. Ask whether the programme offers internships, placements, or live client projects. Opportunities to apply your skills in real situations help prepare you for the transition into work, and programmes with strong industry connections can often see students moving into jobs even before they finish their qualifications.

Finally, look for programmes that understand the realities of creative work. Many creatives switch between employment and freelancing, so the programme should prepare you for both. You’ll want the freedom to explore different pathways and build the confidence to take opportunities when they arise. Ideally, the programme should also offer flexible options so that if you are offered an internship or job while studying, you can take it and continue working toward your qualification.

Choosing the right creative industries training is about finding a programme that connects you with real professionals, teaches the skills employers are looking for, and supports your transition into the creative workforce. With the right foundation, you’ll be well-placed to build a creative career that is both exciting and sustainable.

Vocational training in New Zealand has been on a rollercoaster for years — restructures, closures, shifting priorities, and constant uncertainty. Skilled people have left the sector, and programmes have disappeared. In the South Island regions, the impact is unmistakable: access to hands-on tertiary training is shrinking, and more people are being pushed toward online-only options or relocating to major centres.

These days, every region needs opportunities for people of all ages to upskill, reskill, and adapt to rapid change — from evolving technologies to shifting customer expectations. Industries need capable, creative workers. Communities need people who can step confidently into new roles as the landscape transforms.

And this is where the current structure often fails the regions. Large, centralised institutions tend to move slowly. Redeveloping programmes, responding to emerging needs, designing new solutions — these processes can take years. Vocational training, however, needs to be able to pivot quickly, especially as industries evolve at speed. This is where the regions have historically been strong. Regional communities, employers, educators, and councils have shown time and again their ability to come together, innovate, and create practical solutions that meet their own needs.

When programmes are designed from a distance, without deep connection to local industries or context, they risk becoming disconnected from the very places they are meant to serve.

Vocational training takes a community who understand the region’s realities — its challenges, industries, aspirations, and potential. It requires employers who are willing to partner and mentor. It requires learning facilitators who can deliver programmes grounded in place, responsive to local demand, and flexible enough to support both full-time and part-time learners. It requires iwi, councils, and community organisations who help shape pathways that genuinely reflect local needs.

And crucially, it requires the agility that only communities themselves can create. No one cares more about a region’s success than the people who live and work within it.

That’s why the regions need the autonomy to build their own solutions — vocational pathways that are locally governed, designed, delivered, and able to adapt quickly.

If we want strong, resilient regional economies, we can’t rely on centralised one-size-fits-all models or wait for solutions to filter down from elsewhere.

It takes a community to build vocational training that truly works — and the regions are ready to lead.

When looking for work, do the categorisations drive you crazy? “Are you a curator? A marketer? A manager? A lecturer? An engagement specialist?”

In the Creative Industries, these silos are pronounced. “Are you a content creator? A museum director? A designer? An educator? An artist?” Each discipline has its own expectations, language, and definitions of value — and yet, the work we do rarely fits neatly into a single box. I’ve struggled with this my whole career. I don’t see myself as having one definitive role title. I see problems to solve and opportunities to solve them, and that’s what I’ve always set out to do.

You run organisations, manage budgets, drive income, attract funding and sponsorship, build websites, coordinate, design, and deliver marketing campaigns, manage volunteer and memberships, design and deliver education and outreach programmes, teach, lead teams, support professional development, undertake research, develop, deliver, report on and evaluate projects, propose and implement new initiatives, grow organisations, attract new clients, manage communications … yet in New Zealand, employers often want to pigeonhole skills and knowledge to fit a narrow role description.

The risk is that when we reduce people to one box, we miss out on the full value they bring — the insights, connections, and innovations that emerge when multiple experiences intersect. Imagine if these boundaries didn’t exist. Imagine working across disciplines freely, drawing on the full scope of knowledge and skills people bring to the table.

To employers: look beyond the boxes. Consider the broader skills, experiences, and perspectives people offer — they can make your teams stronger, your projects richer, and your outcomes more impactful.

To anyone whose experience spans multiple areas: articulate it, demonstrate it, and show how your diversity of experience creates real value. Take the chance to be all you can be. Don’t be reduced to a box.

As I sit with my sprained ankle raised, unable to move much, I’ve been thinking about education — and more specifically, how we learn.

How to solve problems and adapt to new contexts is fundamental to learning. Even something as small as working out how to manage daily life with limited mobility has required fast adaptations — getting food, reaching the washing line, navigating stairs. These are small but real reminders that learning isn’t just about absorbing content; it’s about applying thinking in new contexts.

Having been involved in New Zealand’s education system for most of my life — as a student, educator, and leader — I keep returning to one question:

Are we really teaching people how to learn, or just instructing them to meet pre-determined standards based on our experience of education?

We talk a lot about innovation, but too often our systems reward compliance over curiosity. One consistent skill our education system teaches — intentionally or not — is how to follow institutional processes, meet metrics, and navigate bureaucracy rarely designed with learners in mind.

Yes, that prepares people for navigating institutions. But it also reduces learning to procedural compliance. It becomes something you acquire through qualification — tick the box, move on. But real growth doesn’t follow that trajectory.

Staying in your comfort zone isn’t learning. Fighting to preserve a status quo that no longer serves is also not learning. Education can become a trap. We grow confident in what we already know and stop questioning how we know. We become protectionist about the things we learned in the past, convinced that because it worked for us, today’s learners should simply 'take their medicine.'

A colleague recently reminded me: curiosity is too often missing in education. And it matters. Curiosity drives us to explore what we don’t know rather than defend what we do. It invites questions. It fosters exploration rather than just passing on information.

The ability to learn — to think critically, explore creatively, and adapt with agility — is a lifelong skill, not something confined to any classroom. Yet we still prioritise structure over imagination, and assessment over ambiguity.

So, I find myself asking:

Are we preparing learners for complexity, or just for benchmarks?

Are we protecting outdated models because they serve learners — or because they protect us?

Are we resisting change because it feels risky to what we already think we know?

These aren’t easy questions. But they matter. Because if education is to stay relevant, it needs the courage to evolve — and that starts with curiosity.

With art history evolving across education at all levels, I’ve been reflecting on its potential to equip learners for today’s image-saturated world.

At its best, art history has always been about more than artists and movements. It teaches us to read images — to ask who made them, why, and how they became part of art history, including questions of representation and cultural context.

Today, access to images has changed dramatically: they are available on demand, 24/7, across mainstream media, social media, streaming platforms, video games, and AI-generated content. That constant exposure makes the ability to engage critically with images more important than ever.

The democratisation of image-making has also changed the game: anyone can upload a video, create a documentary, design a game, or generate AI content. This raises critical questions for learners: Who created it? Why was it made? Whose perspectives are represented, and whose are missing? What impact does it have on audiences and culture?

At the same time, the reality is that not enough learners are choosing art history, which means its value is often not fully understood. The pathways into creative industries are also complex: over 80% of people working in the sector don’t hold formal creative qualifications, and of those who do, most do not go on to work in the field. This highlights the need for a curriculum that equips all learners with the skills to engage critically with visual culture — whether or not they follow a creative industries pathway.

Some questions I keep returning to:

Should art history continue as a standalone subject, or be integrated into a broader curriculum of visual culture and media literacy?

How can it combine theory, practice, and technology to remain relevant and engaging?

What value does it bring to learners making subject choices with future careers in mind — in design, marketing, journalism, politics, or education?

How do we ensure it develops pressing real-world literacies while maintaining the cultural depth that has always made it meaningful?

Reimagining art history isn’t about replacing it — it’s about enhancing it. By connecting traditional knowledge with contemporary visual culture, we can equip learners with the tools to critically interpret and engage with images across all platforms, from classical artworks to AI-generated content.

The ability to question, decode, and contextualise images is more than an academic skill — it’s a vital competency for navigating the 21st century.

There’s been a lot of attention lately on the productivity of New Zealand’s creative industries, with strong advocacy for more recognition and support. But one barrier keeps us from real progress: the way creativity is siloed as a separate 'sector,' as if it sits outside the real economy.

In truth, creativity is the economy. Every major global brand, from tech giants to food producers, knows this. They invest in design, storytelling, and branding because they understand its direct impact on consumer behaviour, loyalty, and value creation. Think about it: the product you reach for in the supermarket isn’t just a choice—it’s influenced by packaging, colour, typography, and the story the brand tells. The phone you use, the car you drive, your coffee, your clothes, even your home furnishings—they all show how design shapes your decisions, guides your preferences, and influences your experiences.

Even beyond products, the built environment, landscapes, digital interfaces, and media we consume are curated by creative professionals. Our daily lives, often unconsciously, are shaped by creativity—guiding what we notice, how we feel, and the choices we make. Every interaction with a brand, a space, or a service is a small moment of design in action, a deliberate act of influence that contributes to economic outcomes. In short, creativity is not peripheral, it’s the engine behind nearly every transaction, preference, and experience that drives markets and fuels growth.

Here in New Zealand, we still treat creativity as an add-on, something 'nice to have.' The result? We undervalue its contribution to GDP, productivity, and innovation, and miss its critical role in national branding and international competitiveness.

Policy makers, business leaders, and educators have the opportunity to recognise creativity for what it is—essential infrastructure central to driving economic growth, strengthening New Zealand’s global positioning, and building a resilient future.

When creativity is integrated into strategy and investment, it doesn’t just benefit the creative industries themselves. It strengthens every part of the economy that depends on design, storytelling, and innovation to thrive.

Breaking down the silos around the creative industries is essential if New Zealand wants to unlock the full potential of its economy. Creativity isn’t the side show; it’s the main stage.

There is a lot of current dialogue about the removal of art history from New Zealand schools, and it’s prompted me to reflect on my own journey with the subject. I studied art history throughout my education. At secondary school, I can’t say I enjoyed it much (Gombrich and I never really saw eye to eye). But when I reached art school, everything changed. There was more freedom to explore areas that connected directly to practice, to dive deeply into ideas that felt urgent. This re-inspired my interest and showed me how art history could be more than simply a timeline of selected practices, artists and movements.

Reading responses calling for art history to be reinstated in schools makes me curious about the bigger picture. Its decline hasn’t happened overnight — this has been a global trend for decades. I honestly can’t remember when I first joined debates about the closure of programmes and departments, because it feels like they’ve been going on for a long time. If we’ve been aware of this precariousness for so long — with enrolments dwindling and ‘viability’ constantly questioned — what has actually been done to sustain art history as a standalone subject?

That’s the question I keep returning to. How has art history evolved to meet the needs and interests of new generations? Do we understand how people want to engage with it? Should it even still be called ‘art history’? Does it need to be strictly theoretical, or standalone? Can it be integrated with practice? How do we make it meaningful for young people who are making subject choices with future careers in mind — which many do?

Simply advocating for a subject that few want to study — while understandable — doesn’t solve the underlying issue. We need to think creatively about how art history (or whatever we call it) can be made relevant, accessible, and compelling for learners today.

For me, the issue isn’t about reinstating art history in schools but about reimagining it for learners navigating a very different world. What does it need to look like to be compelling and useful today? How can it be contextualised for relevance? And how do we ensure it’s not just surviving, but thriving, as part of our cultural and educational landscape?

We can’t turn back time — so what should art history look like now?

What's the point in Museums? | RNZ

What’s the point in museums?

Museums are often thought of as large buildings in central city locations. In New Zealand, however, the reality is quite different. The majority of our museums are either micro (volunteer-led) or small (1–5 FTE staff), and we have an extraordinary number of them across the country.

This reflects something important: museums are not just buildings. In New Zealand, most of our museums are communities coming together to share and celebrate their arts, culture, and heritage. It is people contributing significant time, money, and commitment to preserving and projecting their own stories. A museum is a purpose, not a building — and that purpose must respond to its place and community.

While our national dialogue often centres on large, centralised museums, it is in the smaller museums embedded in their communities that the true richness of our museum landscape is revealed. All museums have the opportunity to deepen their relevance by ensuring stories are told with communities rather than about them. By creating spaces where people share their own histories and perspectives, museums foster inclusion, connection, and pride.

It is also important to resist reducing museums to a measure of visitor numbers through the front door of the building. So many of our institutions exist because communities themselves created and sustain them. That work is demanding, and it shows remarkable determination: the drive of people across the country to connect, to remember, and to shape identity through story.

The uniqueness of our museum landscape deserves to be recognised, celebrated and shared. It is a landscape built not only on collections, but on incredible commitment and perseverance. It thrives not because of imposing buildings, but because communities — large and small, rural and urban — insist on the importance of telling their own stories in their own ways. That is the point in museums.

There is currently a lot of discussion about the removal of art history from our schools, and yes, I did study art history at school and later throughout my tertiary study. So, while these important dialogues are circulating, I will advocate for what I believe is currently a critical gap in young people’s learning in NZ.

Having had the pleasure of working with thousands of young people making the transition to tertiary education over the years, I have noted a critical gap that is only becoming more urgent: the lack of systematic media literacy training.

Young people are surrounded by media from the moment they wake up to the moment they fall asleep. News feeds, social platforms, advertising, podcasts, influencers, and increasingly, AI-generated content shape how they see themselves and the world. Yet for many, the ability to critically question and navigate this landscape is left to chance.

While some schools offer Media Studies, this is not enough. Media literacy should not be optional—it is a core competency for life in the 21st century. Just as we teach students to read books, solve equations, or understand science, we must also teach them to read the media world they live in every day.

Why does this matter?

Democracy depends on it. A population unable to distinguish credible reporting, misinformation, and AI-driven fakes is vulnerable to polarisation.

Wellbeing depends on it. Young people need tools to recognise harmful patterns and build resilience in the face of persuasive algorithms.

Economic futures depend on it. Every career now intersects with digital and AI-driven communication.

Culture depends on it. Media is where our stories live, identities are expressed, and values debated.

Media literacy equips learners with critical thinking, creative production, and ethical awareness. It asks questions such as:

Who created this—or was it AI—and why?

What techniques or algorithms are used to influence me?

Whose perspectives are excluded?

How does this content make me feel, and why?

Without these skills, we risk raising generations who consume without question, who struggle to separate fact from opinion, and who are unprepared for the realities of an AI-driven society.

The urgent need is clear: media literacy must be embedded across schooling, not as an elective but as a foundation. Imagine if every learner graduated able to analyse both human and AI-created content, create responsibly, and engage constructively in the digital public sphere. The benefits would extend far beyond the classroom—to stronger communities, healthier democracies, and more empowered young people.

It’s time to treat media literacy as seriously as reading, writing, and maths. In today’s world, it is just as fundamental.

Right now:

80% of people working in the creative industries don’t hold formal creative qualifications.

Over 80% of those who do earn creative qualifications do not enter the sector.

This mismatch shows that while our education system produces talented graduates, it doesn’t always connect them to the industry where their skills are most needed. Yet the creative sector is now New Zealand’s fourth biggest export earner, more productive than agriculture, and central to our identity on the world stage.

So what if vocational education became a bridge—connecting learners to the real-world creative economy in all its forms?

Imagine if…

Every qualification is a pathway. Certificates, diplomas, and degrees are stackable credentials completed while in work, rather than requiring long periods away. Institutions act as conduits, co-creating programmes with industry so learning serves both learners and sector needs.

Industry engagement is consistent nationwide. All programmes have industry advisory groups that support a steady stream of emerging professionals transitioning into work. Imagine if embedded, active partnerships were the norm everywhere.

Alumni networks are part of the ecosystem. Alumni who are in industry are connected back to those entering, creating a living bridge where knowledge, mentorship, and opportunity flow both ways.

Education keeps pace with change. Institutions iterate quickly, co-designing micro-credentials & short courses with industry so learners stay relevant.

Mentorship and lived knowledge are embedded. Structured mentoring connects learners to practitioners who pass on tacit skills, networks, and sector insights.

Learning happens in work, not apart from it. The industry itself is the classroom—an incubator of innovation shaping NZ’s creative, cultural and economic future.

Much like any sector, creative industries learning must be grounded in the real world of work. That’s how we ensure learners don’t just earn qualifications—they find meaningful, sustainable careers.

The opportunity is here. The question is: what if we designed creative industries education to be as dynamic, adaptive, and innovative as the industries it serves?

Read the article: Creative sector NZ’s fourth biggest export, more productive than agriculture, report finds | The Post

The word ‘curated’ is everywhere—applied to playlists, menus, even wardrobes. Far from a cliché, this signals aspiration: people are searching for meaning, coherence, and connection. For those developing curatorial skills, it’s an opportunity to shape experiences that go beyond selection, by cultivating literacy in space and place.

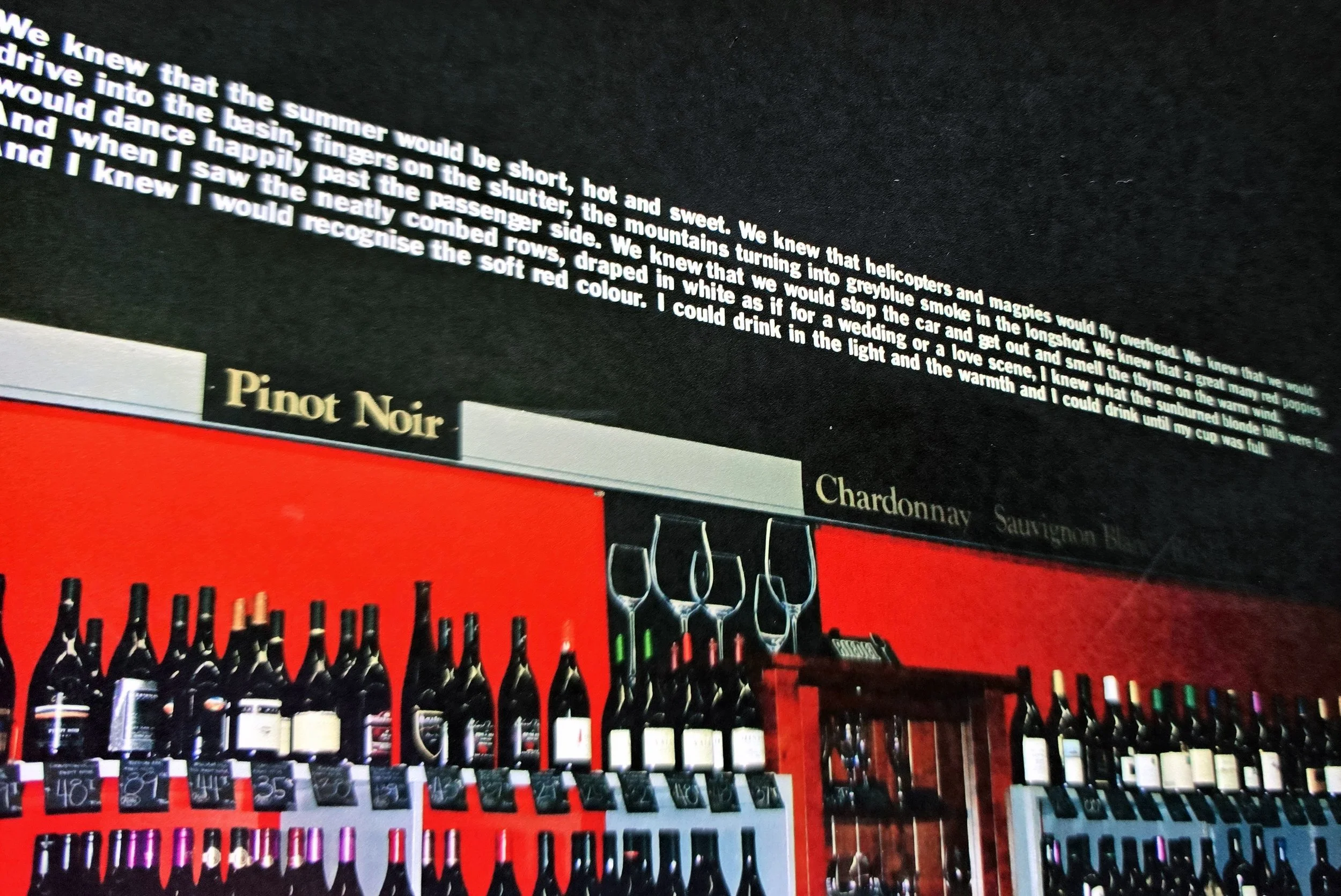

At art school, curatorial practice wasn’t explicitly taught. We explored concepts through theory but were encouraged to follow our own research. For me, that meant interrogating space and place through practice.

Many associate curatorial work with galleries and museums—white-walled, neatly organised spaces reimagined for audiences. This is an important mode of practice; one I also engage with. But it wasn’t where I began. Those spaces were largely inaccessible to emerging professionals, so I started working across unconventional sites—cafés, offices, public spaces, empty retail venues, and community billboards.

What I learned was pivotal: curatorial practice isn’t about portable objects slotted into blank spaces. It’s about using space and place as a medium, transforming environments into context-specific experiences for the people who move through them.

This applies beyond cultural work. The spaces we traverse daily are curated to some extent, shaping how we navigate and engage with the world. Curatorial skills sharpen our ability to read these environments and reshape them for meaning, accessibility, and connection.

Curatorial skills are often undervalued outside of museum environments, yet they translate across industries:

🔹 Spatial literacy: Reading and interpreting environments to shape them for accessibility, equity, and representation, so more people see themselves reflected.

🔹 Contextual storytelling: Weaving narratives and ideas inseparably with space and place, anchored in histories and communities.

🔹 Audience-centred engagement: Recognising that spaces are lived and felt, adapting experiences for resonance and connection.

🔹 Cross-disciplinary collaboration: Engaging architectural, historical, social, and cultural knowledge to enrich place-based work.

🔹 Ethical responsibility: Considering whose stories are privileged, whose are absent, and how authority is exercised in space, place, and experience.

For emerging professionals across creative and cultural industries, practice-based curatorial experience is invaluable—shaping context specific physical or digital experiences. It builds adaptability, co-creation skills, and the ability to frame meaningful encounters through space and place wherever people engage with ideas or stories.

In a world saturated with content but hungry for connection, curatorial literacy offers a way forward. For me, it began with transforming overlooked sites. Today, the opportunity is wider: to use curatorial skills to connect people, place, and meaning wherever they meet.

Artwork: Rainy McMaster (in Dunedin bottle store).

Museums have always been producers of content and education. But there’s never been a better time to capitalise on the shift away from centralisation toward more dynamic, diverse ways of connecting with audiences. Whether your museum is volunteer-run or equipped with a professional production team, the opportunity is now. With limited and low-cost tools, even the smallest museum can reach a global audience—no matter how niche its collections or stories.

And if your organisation lacks expertise, there is an incredible diversity of free online resources to help you get started. You can also engage digital natives through internships or placements—essential pathways for young professionals to hone their craft and build new skills. Your museum has value, and it’s time to recognise it.

The Tank Museum shows what’s possible when a museum fully embraces video. With a professional production team, it has built one of the world’s most successful museum YouTube channels—transforming a highly specialised subject into global entertainment and education. I never imagined I’d find the history of tanks so compelling until I engaged with their content. That’s the power of storytelling: it makes people care about subjects they never thought were for them.

This shift speaks directly to education. Learners today expect to design their own journeys—choosing what, when, and how they engage. Centralised classroom-based education has significant limitations, creating a gap that museums can fill. Want to understand the gaps your museum could address? Engage with your communities, listen to their needs, and build learning solutions that matter.

The possibilities are rich: educate and entertain through video, create immersive experiences with animation, gamify learning to make it interactive, collaborate with education providers, offer modular online courses, hybrid models, flexible pathways, or short stackable modules. When developing your content strategy, remember media and entertainment have a lot to teach us about audiences and storytelling. Watch, learn, and adapt. Museums—keepers of deep knowledge—can deliver compelling, relevant, and globally accessible content that meets audiences where they are.

The opportunity is here, and the movement is already happening. Will your museum choose to be part of it?

#MuseumInnovation #DigitalStorytelling #OnlineEducation #GamifiedLearning #CulturalInfluence #FutureOfMuseums

As funding models tighten, the strength of arts, culture, and heritage increasingly depends on community-driven, decentralised approaches. By embracing diversity and collaboration, regions can turn cultural assets into stories that resonate locally and globally.

In Catalonia, the Barcelona Provincial Council Local Museum Network brings together 65 museums across 51 municipalities. The network fosters a dynamic, multidisciplinary museum model, turning museums into accessible public service centres. By collaborating across municipalities, they pool resources and expertise, creating richer exhibitions, broader audiences, and a stronger regional identity.

In Massachusetts, the Berkshire Arts and Culture Alliance (BACA) unites ten major institutions, including MASS MoCA and the Norman Rockwell Museum. With a combined budget of $212 million annually, mostly from philanthropy and earned income, BACA attracts 1.7 million visitors yearly, generating around $1.5 billion in economic impact. Collaboration strengthens cultural infrastructure and tourism while boosting the local economy.

In Andhra Pradesh, India, the Kondapalli Bommala Experience Centre celebrates the village’s artisan-made wooden toys. Through tours, demonstrations, and educational programs, local artisans, authorities, and educators collaborate to preserve and share traditional knowledge, positioning Kondapalli as a national example of rural creativity and self-reliance.

These cases show how decentralised, collaborative cultural ecosystems enhance regional identity, drive tourism, and engage communities. Sharing resources and expertise allows institutions to achieve more collectively, while elevating cultural presence globally.

Investing in these networks is essential. By empowering local institutions and fostering partnerships, regions can build resilient cultural identities that thrive locally and internationally. Collaboration isn’t just a strategy—it’s the foundation of sustainable, vibrant cultural ecosystems.

#CulturalCollaboration #Decentralisation #RegionalIdentity #CulturalTourism #CommunityEngagement #GlobalVisibility