After returning from a week working in Southland, it has been a pleasure to spend time with publications from John McCulloch’s archives as part of research for the exhibition 'Drawing Together: John McCulloch’s Community Architecture.' I am certainly not an expert in architecture, but, like many, my relationship with it is personal. My mother, an interior designer with a passion for architecture, collected books that allowed me to explore space and design as a child. My parents’ second‑storey extension to our first family home in Dunedin included my mother’s lead‑lighting studio, where stacks of imported coloured glass and feature windows she made revealed the material and social possibilities of architecture.

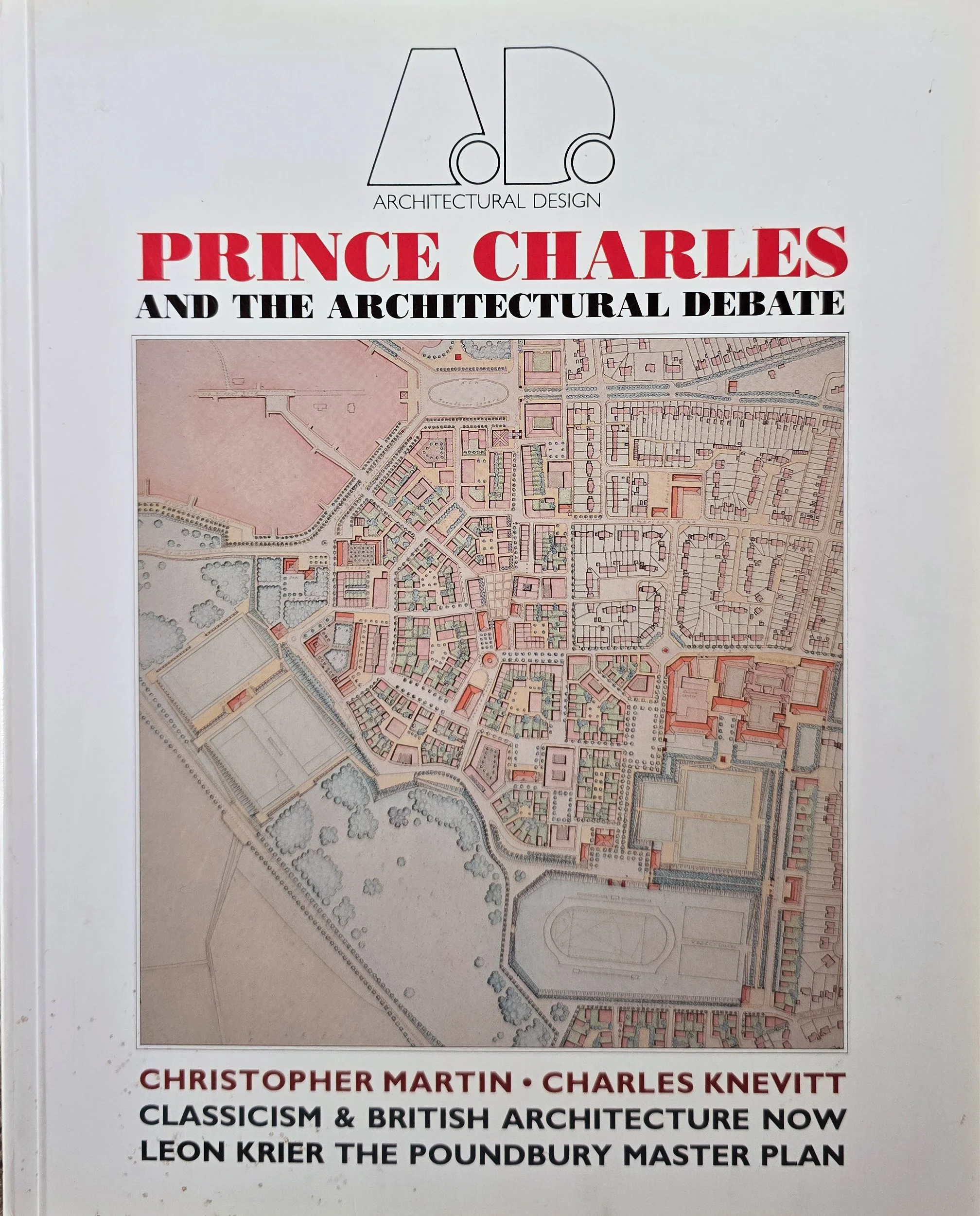

Through McCulloch’s archives, I am reminded that architecture shapes how we live and move, framing routines, interactions and a sense of belonging, often without conscious awareness. This issue of Architectural Design shows his engagement with debates shaping late twentieth‑century architecture.

Christopher Martin’s essay 'Second Chance' revisits the Prince of Wales’s 1987 Mansion House speech, his BBC film A Vision of Britain, and the 1989 V&A exhibition. McCulloch’s interest in these debates reflects his concern with human‑scale, context‑sensitive architecture. The Prince critiqued modernist redevelopment for erasing historic streets, squares and mixed‑use neighbourhoods, and argued for continuity, craft, and public engagement in design.

A bookmarked article, 'New Town Ordinances & Codes' by Duany, Plater‑Zyberk, and Chellman, likely noted by McCulloch because of links to another archived article by Duany, critiques regulations that prioritise traffic, parking, separated uses and low density. The Traditional Neighbourhood Ordinance they propose purports to reduce car dependence, and support social interaction, civic life, and a mix of housing and local commerce — principles McCulloch explored in his own work.

Richard Rogers’ 'Pulling Down the Prince' offers a counterpoint to A Vision of Britain, arguing that architecture reflects social, economic, and technological conditions. Traditions now revered were once radical. Rogers emphasises adaptability: buildings must change function while keeping coherence, a principle evident in McCulloch’s context‑sensitive design.

These perspectives intersect in McCulloch’s archives and practice. As Rogers notes, “once great centres of civic life have become jungles where the profiteer and the vehicle rule” (Architectural Design, 1989). McCulloch’s advocacy for walkable, mixed‑use communities and responsive design reveals an understanding of these issues that is practical and philosophical. This publication, as an artefact of his engagement, and in the context of 'Drawing Together', captures a moment in the ongoing conversation about continuity, adaptability, and civic life, showing why architecture, as McCulloch understood it, remains inseparable from the way we live.