When I was at art school, I lived off a student allowance, which meant a very lean life with little room for expenditure beyond rent, power, phone, and food. I didn’t have internet at home, or my own laptop. I made black coffee in a pot on the stove, later upgrading to a stovetop coffee brewer I found for $2 at an op shop. I slept on a mattress on the floor with a broken bed base, owned an old antique dressing table, and put cash into jars each week to make sure I could keep the power and phone on.

Most winters I froze and went to bed fully dressed, wearing a beanie and using two hot water bottles. My first flat was a concrete-block, two-bedroom unit with a one-bar heater. Each morning I woke to condensation streaming down the walls. I owned an old second-hand television that worked sometimes but had an ancient video player that worked just fine—aside from the occasional moment when I had to unscrew the top to rescue a chewed tape.

There was a shared washing machine with two tubs, requiring mid-cycle load swaps. I walked long distances to art school, to buy groceries, pay bills, and visit op shops, only occasionally taking the bus. I kept spare clothes in my locker at school because arriving soaked was not uncommon in Dunedin.

None of this felt unusual. And this isn’t a story about hardship—I was happy. I was making my own way in the world and had the opportunity to attend art school and learn from people I admired. I became an avid op shopper and attended auctions, amazed by how much could be acquired for so little.

I committed fully to painting and took every opportunity to do commissioned work: portraits of children, pets, houses, and gardens. When I started, I had two paintbrushes and three colours—black, white, and red. I made my own canvases at art school. Later, a local art supply store allowed me to open an account, paying $10 a week so I could gradually buy more brushes and colours. I painted constantly, developing strategies to work with what I had.

For a large-scale commission, I woke at 4am to paint for three hours before my flat mates woke. The canvases were too large for my bedroom, so I unpacked and repacked them daily.

I didn’t need much to begin. I worked for years with a 35mm camera a friend loaned me, bought 120mm cameras at auctions, and still use two old tripods—one bought for $15 thirty years ago, the other found abandoned.

Limitations became my greatest ally. The skills I learned served me well when I took my first paid role in the non-profit museum sector, where budgets covered little beyond salaries and modest programme costs. Fundraising was routine, and doing a lot with a little was simply how things were done.

Creativity thrives on constraint. Limitations force choices, sharpen focus, and build resilience. Working with less taught me how to begin, how to persist, and how to solve problems rather than wait for ideal conditions. Abundance, by contrast, can often be a hindrance to creativity, encouraging hesitation, distraction, or the pursuit of perfection. These lessons continue to inform my creative practice, reminding me that meaningful work rarely depends on having more but just on getting started.

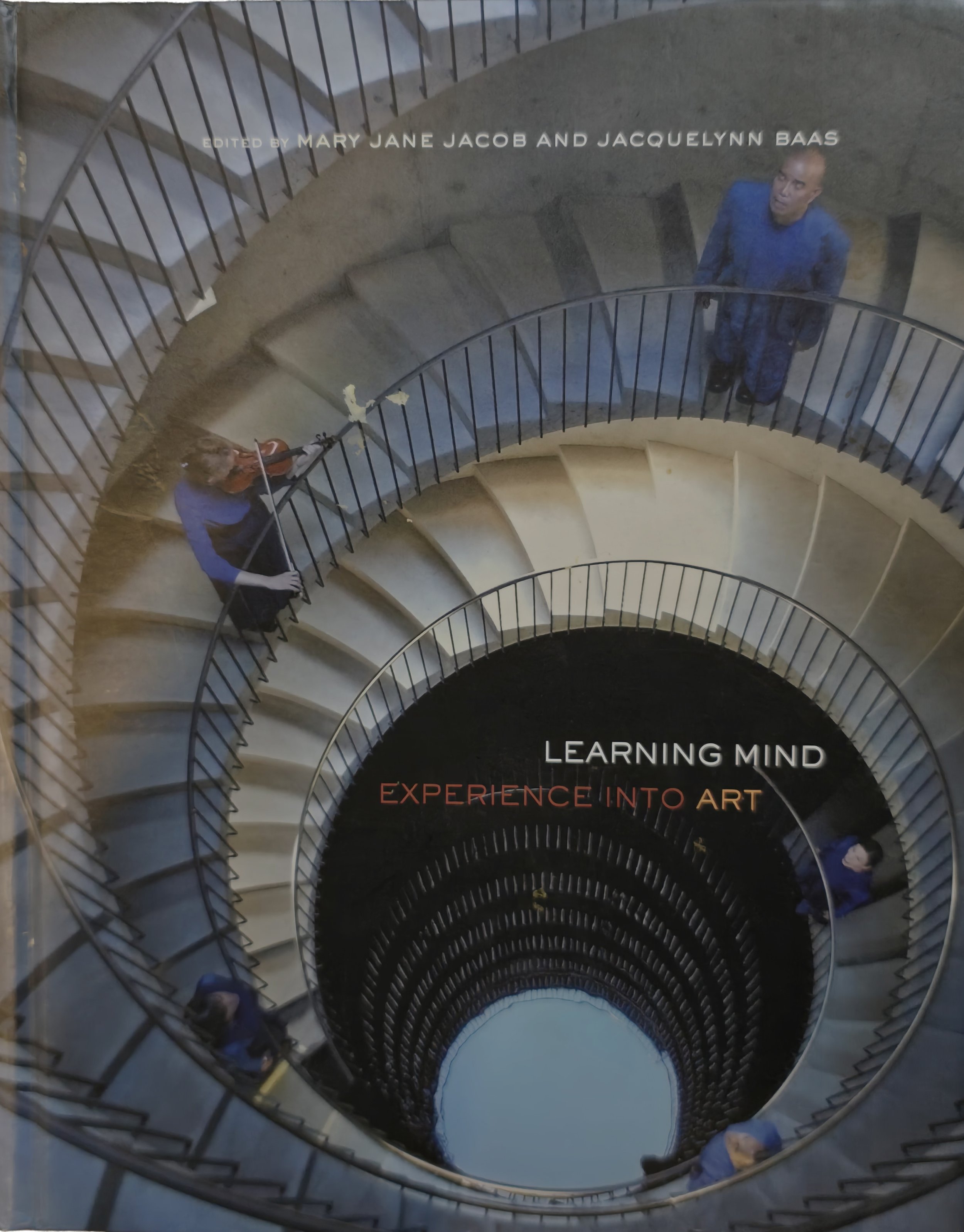

Commission for Dunedin Hospital, 1999.